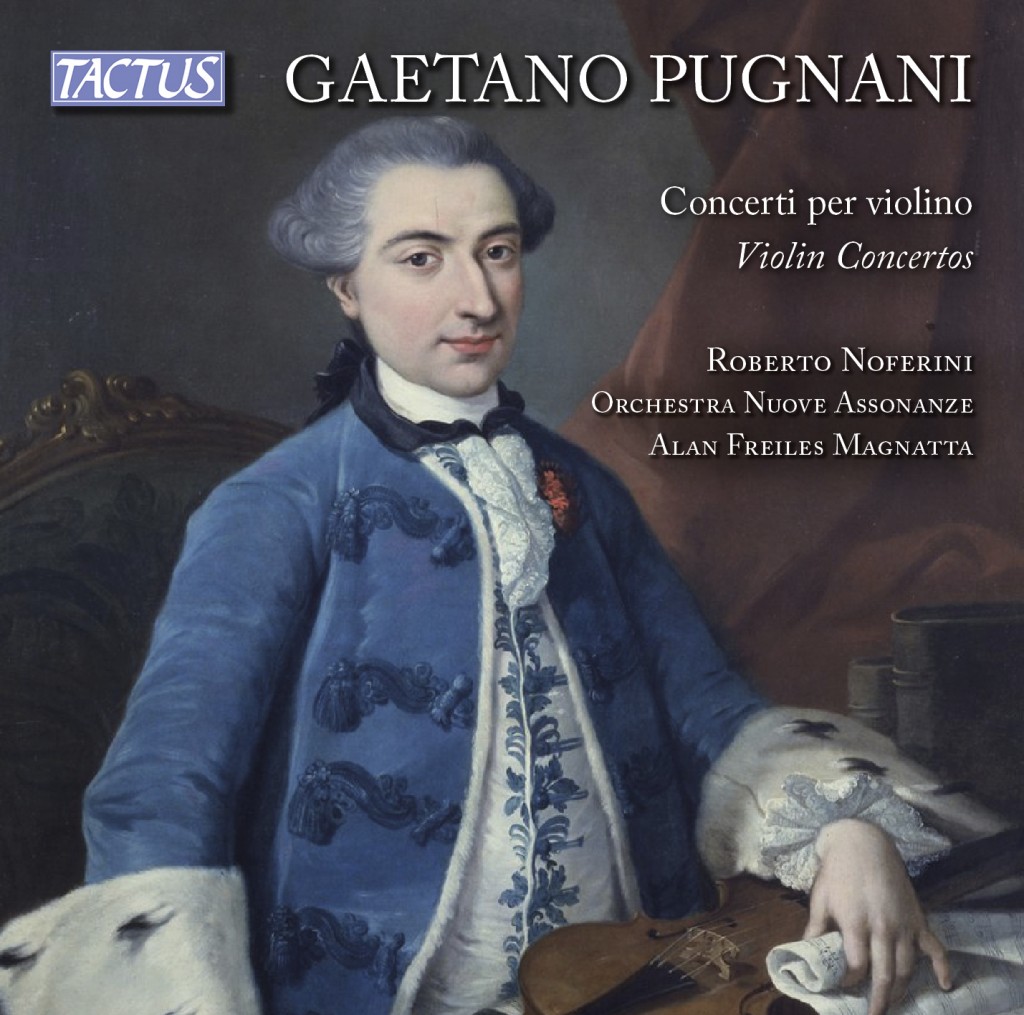

Compositore: Gaetano Pugnani (1731-1798)

Composer: Gaetano Pugnani (1731-1798)

Titolo: Concerti per violino

Title: Violin Concertos

Esecutori: Roberto Noferini, violino Orchestra Nuove Assonanze Alan Freiles Magnatta, direttore

Performers: Roberto Noferini, violin Orchestra Nuove Assonanze Alan Freiles Magnatta, conductor

Buy

Buy

Review Jonathan Woolf - Cd Pugnani - Violin Concertos

It’s perhaps unfortunate that for so long Pugnani was better known for Fritz Kreisler’s appropriation of his name for the Austrian’s own Praeludium and Allegro than for his own raft of attractive and distinctive pieces. Pugnani was an important, pivotal figure. He was a pupil of Giovanni Battista Somis – who had been a pupil of Corelli – as well as of Pasquale Bini, and Pugnani later taught Viotti. In Pugnani the Corellian and the Roman traditions (the latter via Bini) fused.

As an eminent violinist, who played across Europe and Russia he was perfectly placed to write for his own instrument. Sonatas for two violins and single violin sonatas with continuo have been recorded but the large-scale works have fared altogether less well. The two violin concertos here are heard in world premiere recordings. The D major concerto was found by Adam Rieger in the Nauk Library of Krakow in the 1970s. The manuscript was not in the composer’s hand but had been copied by none other than Jean Jacques Rousseau, a frequent transcriber of scores.

Pugnani’s writing was adventurous. He wasn’t afraid to take the soloist high, nor did he stint virtuosic passagework. Above all, he was a real melodist, and one predicated on vocalised cantabile. All this makes for delightful and rewarding listening. The D major is graced with an avuncular orchestration that launches the soloist’s silvery passagework; clever, clean, clear and formally accomplished. There’s a fine orchestral lurch into the first movement cadenza, which is the work of soloist Roberto Noferini. With a beautifully poised slow movement, with the soloist singing over an expressive orchestral cushion, one relaxes into the luxury of a bel canto few minutes before the orchestra suddenly and surprisngly breaks into pizzicati, driving the soloist into still more operatic richness. The buoyant finale seems to quote Locatelli in the ‘a capriccio’ section.

The companion work is cast on a somewhat broader canvas with the horns prominent in the balance and the oboes singing clearly. There is much to catch the ear, such as the lyrical exchanges between soloist and orchestra – real dialogues not merely supportive orchestration – and in the Largo an expressive song so good it could have been a slow aria in an opera by Porpora. The lyric pathos of this movement is followed by the aerial devilry of a spirited finale, with at one point the soloist in a whirligig of perpetual motion.

The band lines up 4-4-2-2 with two oboes and two horns and plays on modern instruments. The church sounds relatively large but the small ensemble, expertly directed by Alan Freiles Magnatta, expands to fill the acoustic well and there’s no blunting of attacks or accents. The recording works well in fact. Noferini is a stylish, stylistically elegant soloist, clean of attack, generously lyrical, secure in alt.

With excellent booklet notes into the bargain this is a valuable addition to the catalogue of eighteenth-century Italian concertos on disc.

Jonathan Woolf (http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2018/Jan/Pugnani_VC_TC731601.htm)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Review Jonathan Woolf - Dvd D' Ambrosio - Violin Concertos

Alfredo d’Ambrosio has always held a toehold on the repertoire of violinists via his morceaux, notably the Canzonetta and the Serenade. In pre-war days some of the elite of the profession recorded some of his works - Heifetz, Elman, Tertis, Sammons and Thibaud led the way though D’Ambrosio himself, an attractively small-scaled and salon-orientated player, also recorded a raft of his own works. A few other similarly light and charming pieces are occasionally dusted off by the adventurous recitalist looking for fringe repertoire. Peter Fisher, for instance, recorded both the Serenade and Canzonetta adding the Romance, Op.9 and Sonnet Allègre on his Litmus CD.

Now there is something altogether bigger. Though a cassette-made recording exists of the great Aldo Ferraresi performing Concerto No.1 , here is a chance to see filmed performances of both concertos the Neapolitan-born composer wrote, the first in 1903 and the second a decade later. They were recorded at the same concert in Lucca in October 2018, with two excellent young soloists, and the Orchestra Nuove Assonanze directed by Alan Freiles Magnatta.

Recorded in the beautiful Chiesa dei Servi, the camera direction is straightforward and unshowy and focuses on the musical matters, rather than panning or cross panning architecturally. The soloist in the First Concerto, written for Arrigo Serato, is Laura Bortolotto, whom I’ve heard before in Spohr and in a filmed performance of Antonio Illersberg’s concerto which, like the d’Ambrosio, can be found on the Achord Pictures label. She plays with romantic expression, without a score, fully surmounting the tests of the opening dramatic recitativo – it must be a slightly unnerving experience for the soloist to be pitched into the concerto in this way – and displays much lyrical beauty and technical security. She maintains a fine body of tone throughout and revels in those Bruch-like moments of ripe amplitude. Contemporary critics may have grumbled about the work’s length, implying prolixity, but in a performance such as this one can listen without reservation, not least to the canto popolare-like richness of the slow movement and the dashing bravura of the finale.

The 1913 Concerto was dedicated to Jacques Thibaud but premiered by George Enescu. In conception and construction, it shows a somewhat more advanced outlook but retains the composer’s characteristic lyric quality. Christian Sebastianutto plays a 2018 fiddle and, unlike Bortolotto, plays from the score. One reason might be that the Second is even less well-known than the First Concerto. In fact, this is, I believe, its premiere recording in any form. Again, the soloist dives straight in, and whilst the orchestration is much more robust there is something slightly Franco-Delian about some of the writing. With greater fluidity than the 1903 concerto comes a more marked sense of flux and with tell-tale use of the harp in the ripely romantic slow movement, which ripples away delightfully, this is as engaging a concerto as the earlier one. The terpsichorean finale embeds a lovely lyric B section which Sebastianutto plays well.

The booklet is simply but well produced, in Italian and English, and the production generally fully supportive of the project.

These are d’Ambrosio’s biggest and ultimately most important works. Studio recordings by these artists would doubtless bring the works to a somewhat larger audience but for those intrigued by the repertoire there’s much to be enjoyed in these youthful, pliant performances.

Jonathan Woolf (musicweb-international.com/classrev/2019/Jul/Ambrosio_VCs_Achord.htm)